In both subtle and direct ways, my mom taught me it doesn’t matter if you’re pretty or have a boyfriend; what matters is if you’re smart, strong and capable. Women who rely on their looks, a man or God are weak. Women who use their brains are free and powerful.

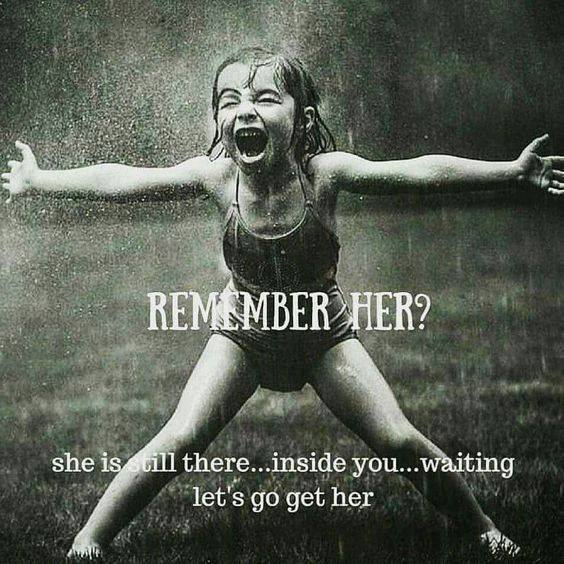

I never felt free, powerful or smart as a kid. To this day, I don’t know if when I was young my mom believed I was smart, but lazy or if she thought I wasn’t smart and it frustrated her to think she and my dad’s brains combined should’ve created more. She used to scream when I did something she didn’t like (as if I could predict what that would be). “Alice Ann! You’re not stupid!” I tried harder not to be.

At school, looks mattered. When you’re the ugly kid, the mirror repulses and the looks from other kids shame.

Looking at my mom, I think she hid her beauty, the way some women exploit theirs. I wasn’t hiding my beauty any more than my brains. I was ugly. As a little girl, I wanted to be a boy. I thought I knew how to be a boy.

I didn’t know how to be pretty. No one taught me. Even the most naturally beautiful are rarely recognized until they’re groomed. Mothers teach their daughters to groom, like fathers teach their sons to play sports.

Not in our house. The answer to every question, I was told, could be found in a book. From my perspective, my parents didn’t give credence to the human heart or any sort of spiritual knowing. In fact, both my parents were so smart they knew there wasn’t a God.

They sent me out to churches with friends so I could see for myself. Somehow, intended or not, I got the message that what I was supposed to see was just because they believe in God, it didn’t make them bad. They’re maybe just not as smart was the message. Is that any different from They’re not as educated or as wealthy or well-bred? Wasn’t it just another form of “We’re privileged and we’re proud,” whether it was true or not?

The truth adhered to in our house was tolerance. Decades later, I’d learn tolerance is a distance from acceptance. I was free to choose whatever I wanted to believe, which was supposed to be better. As it was explained, Christian children are told there is a God, like my parents once told me there was a Santa Claus. The poor deprived Christian children never got to choose. Choice was a gift.

Imagine me in 4th grade, scrawny girl who may or may not have combed her hair or brushed her teeth that morning, wearing goofy glasses and clothes from People’s Department Store (which wasn’t a thrift store, but sure didn’t sell style), hanging on the playground, explaining my families’ religious philosophy to a gang of kids heckling me.

That day, especially, ugly mattered. All that thinking, evaluating and deciding I didn’t believe in God didn’t make me feel free or powerful.

Later, as an adult, I’d look back and know that yes, for me, choice worked. It worked for me to develop my relationship with God based solely on our communication, not on reading the handbook, attending the meetings or participating in the philosophy.

God and I just found each other when I was a kid. He’d hang out with me, convince me not to jump off cliffs or run too far from home. He comforted me and often carried me. It was just He and I. I didn’t discuss my relationship with God with my Christian friends, although I occasionally went to holiday services with them. Saying I believed in God out loud felt like betraying my parents.

Plus, I kind of liked the McGrath family, with 10 kids, trying to save me. It meant I always had a place at their dinner table.

I stayed with Theresa McGrath in my late 20s while working in Tulsa, OK. The McGraths are the rare family who live their Christian faith—in their businesses, their families and their excessive successes. They’re American Christians.

“This is what we know to be true, Alice. Jesus Christ died for your sins and unless you believe in Him and follow the Bible’s teachings, yes, you will go to hell. I know you love your parents, but they will go to hell. I’m sorry. That’s just the way it is. Read the Bible.”

I read the Bible the way most people do, picking and choosing the parts I liked the best.

I’d long since announced my faith in God without much apology or explanation. The McGraths seemed to believe I was a beautiful child of God who needed their protection. Theresa, by that time, and by the grace of God and American opportunity, had built a successful salon business.

During the six months I stayed with her, she transformed my appearance, catching me up on a lifetime of beauty tips. Oh, I’d mastered the curling iron and mascara, but I never imagined spending $10 on a lipstick.

During my work time (10 days on) I stayed with Theresa. During my off time (4 days off) I lived with my mom. By then, I’d grown “successful” in my own male-dominated field—sales. I’d done my parents proud, in spite of not having a college degree. I presented myself to the world as, “I may not be the smartest and I may not be the prettiest, but I’ll work harder than anyone and learn whatever I have to because I am a strong woman.” Can you hear my parents clapping? I did, and oh, how it made me dance.

While I danced and worked, Theresa did my hair, taught me skin care, what styles were in and where to shop. When I came home, I visited my mom, who lost her job at age 55 and hadn’t been able to replace it, even with that PhD in her pocket.

I became beautiful before her eyes, and for once, she wasn’t too busy to look. To my mom, beauty had always been a frivolous pursuit. She stood blown away by how it looked on me. She savored my beauty, the way one does when falling in love with a new food she never intended trying.

Beautiful, strong, spiritual 28-year-old me watched my mother’s physical strength succumb to cancer. I knew it was bad when she couldn’t read a book. After she died, I found a scrapbook of hers, filled in with goals, quotes and affirmations. God, surprisingly, was included in her plans. That was beautiful. And, damn, she was smart.